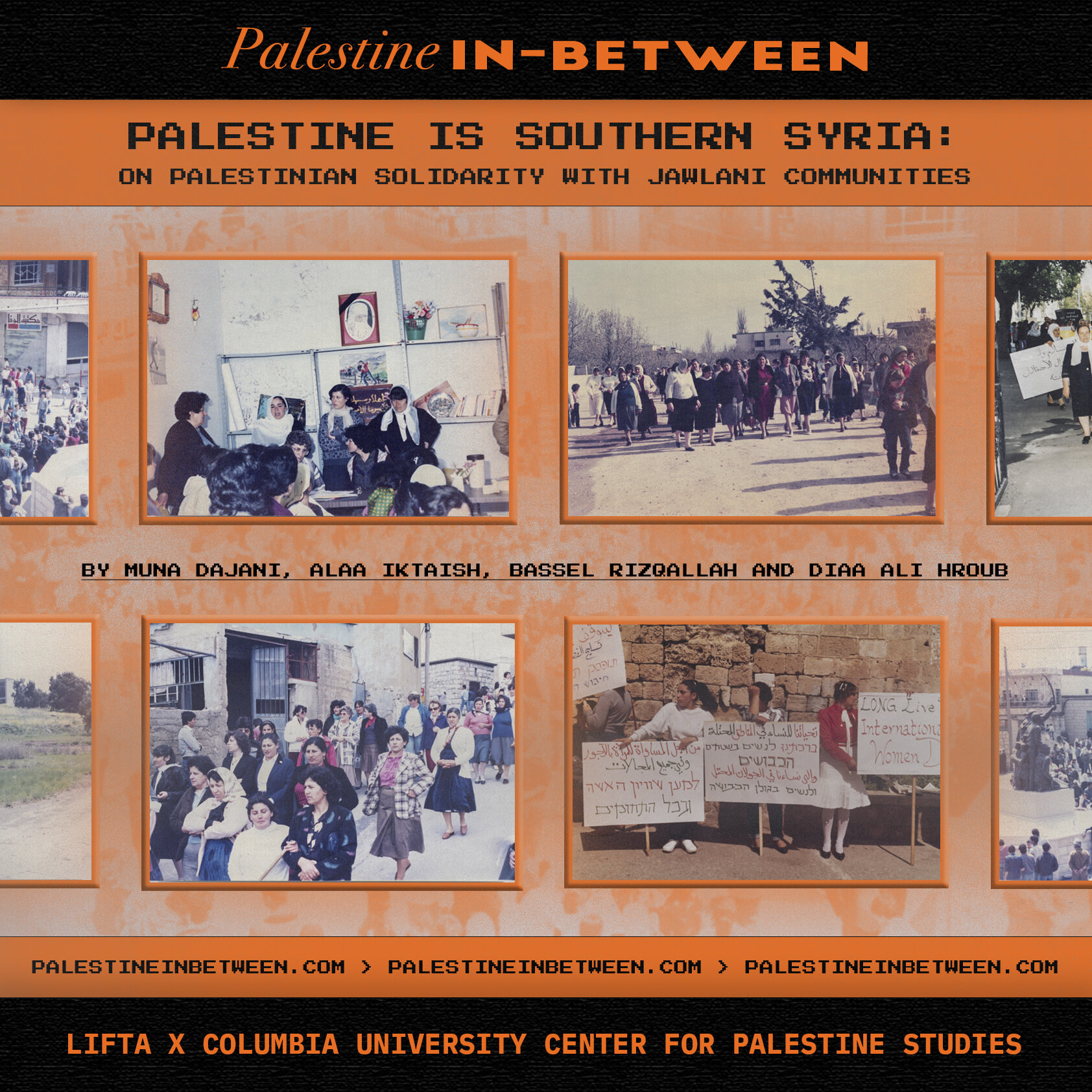

Palestine is southern Syria: On Palestinian solidarity with Jawlani communities

by Muna Dajani, Alaa Iktaish, Bassel Rizqallah and Diaa Ali Hroub

Our project, Mapping Memories of Resistance in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights (1), is an ongoing collaborative effort between academic institutions, activists, artists, and students who are interested in narrating, documenting, and re-telling stories and experience of living with, resisting, and enduring forms of political, socio-economic and cultural domination. The project forms part of the Academic Collaboration between the Department of Geography and Environment at LSE, the Israeli Studies MA program at Birzeit University in Palestine, and Al Marsad Arab Human Rights Centre in the Golan Heights. The overarching theme of the project is examining transformational events in the lives of communities under settler-colonial rule in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights. We examine the trajectories upon which the Jawlanis have embarked on following the great strike (الاضراب الكبير); a six-month strike in the Jawlani villages in 1982 protesting the unilateral Israeli annexation of the region and the attempt to force Israeli citizenship on the remaining Jawlani community. Our project took us on a journey of learning, unlearning, active archiving, brainstorming, and sharing ideas and reflections on how this event continues to be a ‘live’ event. What has been brought to the forefront of those encounters was the centrality of the shared experiences of solidarity and support that Jawlanis and Palestinians engaged in on multiple fronts.

The 1948 Nakba and the Naksa of 1967 are dates in history that are etched in the memory of Palestinians and Jawlanis alike as a year of dispossession, uprooting, defeat, surrender, and betrayal. Nineteen years after the Nakba, the 1967 Naksa expanded the settler-colonial territorial expansion, colonization, and the ethnic cleansing of the rest of Palestine (namely East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip) and the Syrian Golan Heights. Our approach in this project has not been to extend our focus to the monumental years and events of the Nakba and Naksa, but to focus on what has been framed as the ‘Shadow Years’ (2). ‘Shadow Years’ refers to the time following the Nakba and Naksa for those Palestinian and Syrian communities who remained in their towns and villages. They had to make sense of the material uprooting they endured from their lands and the abrupt deformation to their societies and way of life, putting them at the forefront of an encounter with a settler-colonial state. During these shadow years and as the settler colonial systematic uprooting intensified, communities mobilized, resisted, and collaborated with each other to solidify relations and build collective resilience.

This photo essay and the mapping project aims to initiate a recollection of testimonies, memories, and strategies of collective struggle, resistance, and resilience (sumud) that Palestinians and Jawlanis engaged with in their collective struggle and encounter with Israeli settler-colonial rule. We shed light on how this solidarity has shaped the Palestinian and Jawlani struggles and how we see its pertinency to inspire and invigorate future generations to reimagine new pathways of action.

* Scroll to bottom for footnotes

Nazeeh Abu Jabal on early Palestinian-Jawlani solidarity: “protect your land!”

Nazeeh Abu Jabal is a walking encyclopedia and a great storyteller. His sharp memory and love for history, as well as his local knowledge of the land, takes one on a vivid journey of the past. The story of the Jawlan after 1967 is filled with contrasting feelings and experiences. The Jawlani community was uprooted from its Syrian roots and forced to accommodate a new regime of settler-colonial rule, a new language and lexicon, a new currency, and a military rule that aimed to expropriate and exclude them from the means of production and political identification and belonging.

A picture of Majdal Sham with a sign in Hebrew/English in 1974 (3)

The Jawlanis’ triumph against these impositions described above could not be illustrated more clearly than with how the remaining villages’ lands were reclaimed, parceled, and transformed, creating the iconic landscapes of apple orchards in Majdal shams, Masada, Buq’atha, and Ein Qinya. Nazeeh’s recollection of the monumental efforts of the Jawlanis to protect their remaining land from confiscation brings to the forefront the role of Palestinian counterparts who alerted the Jawlanis to the creeping threat of land confiscation, as Nazeeh shares (4):

“After the 1967 occupation, we were able to be in touch with our friends and extended families inside Israel in Rameh and other Druze villages. One of our main concerns and inquiries were about the Israelis and how to deal with them and we sought their advice. Their first advice was: take care and protect your land. Any land left barren and uncultivated is going to be confiscated by the state. Water, springs, wells are going to become state property. You have to be strong and protect your land and water to preserve your existence. They shared with us that the Israeli state left them with no land and water through laws they imposed during the military rule. In the following months, we continued receiving more knowledge and advice from them on how to tackle the Israeli policies aimed at controlling our land and water. My father sat down with his friends and I was there. One friend advised: any land that is designated as Syrian state land such as forests, if not utilized by you Jawlanis, will be turned into Jewish settlements. One of those areas is Al Balan – an area between Majdal Shams and Masada. You should bring bulldozers to take out the forest and plant apples, there will be a lawsuit filed against you but the law states if you plant it for two years then you will definitely win the case. Plant any uncultivated barren land.”

Nazeeh Abu Jabal in his apple orchard in Al Marj, Majdal Shams (Photo by Muna Dajani, 2017)

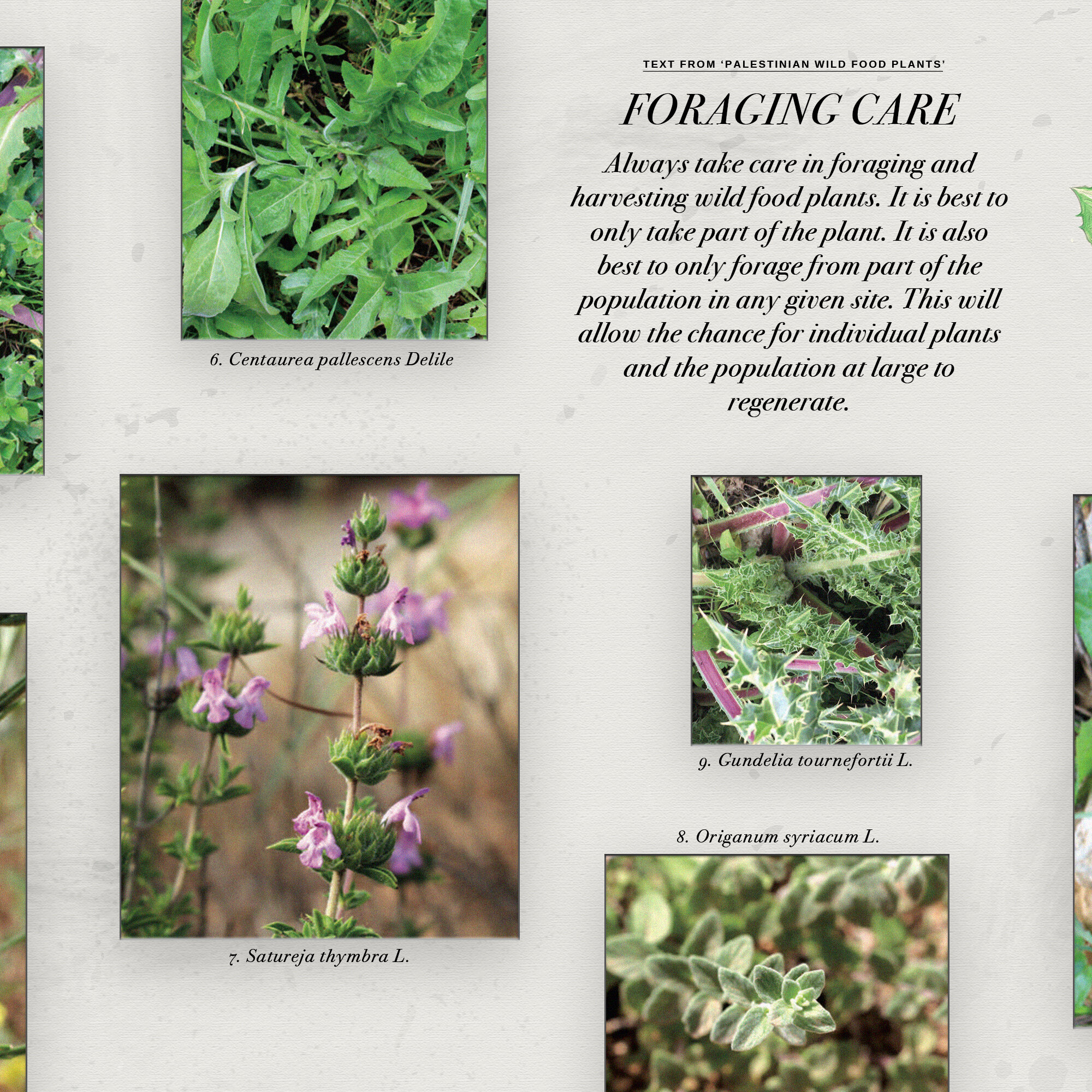

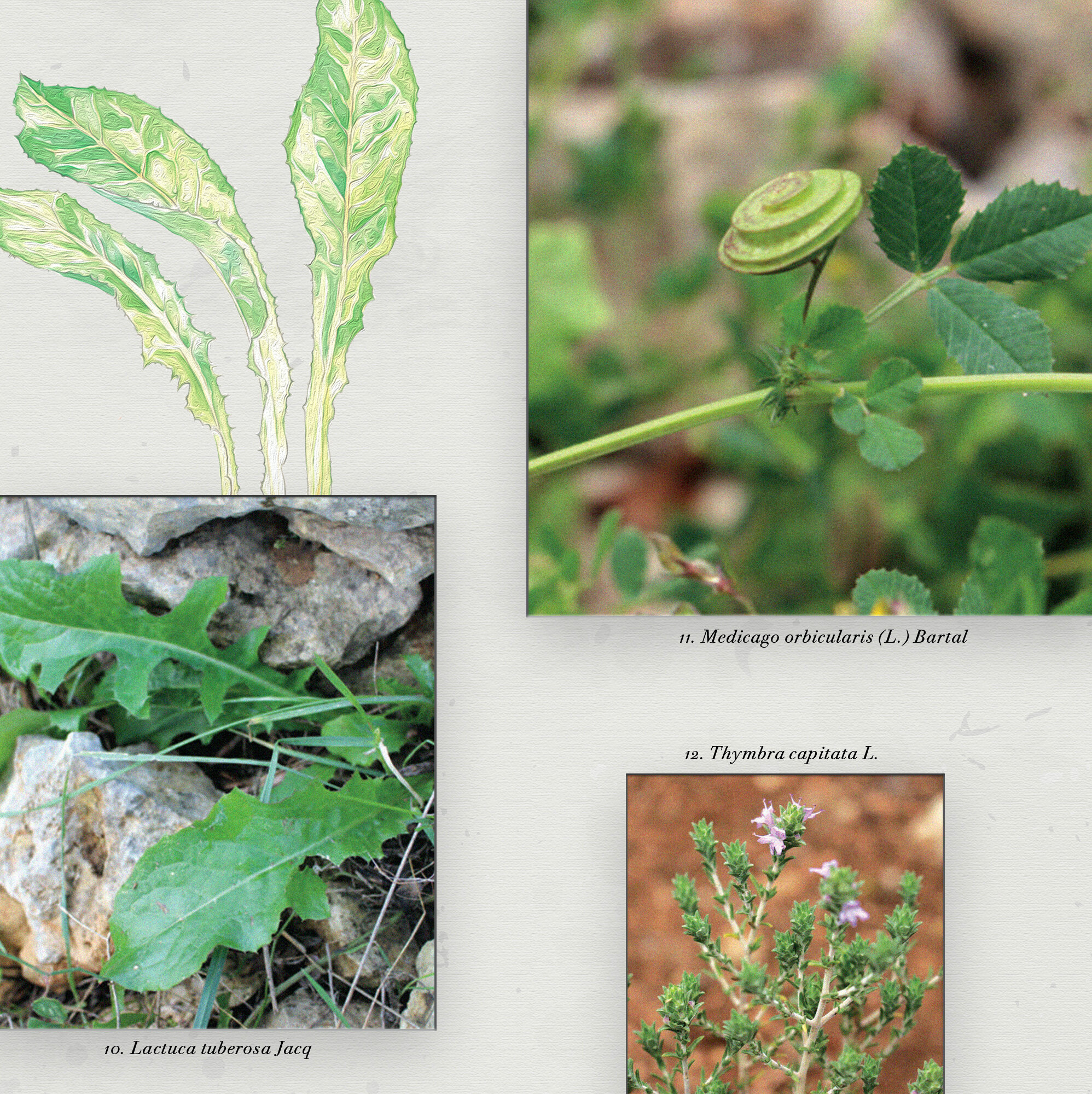

Samira Khoury: women solidarity for justice and peace

This summer, Samira will be 93 years old. She was born in Nazareth in the Galilee, situated in northern Palestine. She dreamt of becoming a teacher all her life and her path in teaching began when she enrolled in “Dar el-Muaalimat” college in Jerusalem. Samira studied in Jerusalem for five years (1942-1947), then she worked in Akka until 1948. During the Nakba, Samira returned to Nazareth and got married. Her marriage to Abu Jaber introduced her to the Communist party, where she became more assertive in advocating for the collective rights of her community. The Israeli authorities suspended Samira and her husband from teaching in the public schools because of their political activism but she found another avenue to continue to advocate for Arab women’s rights. Samira and around 80 other women members of the Communist party decided to organize their work activities under a formal body called al-Nahdah al-Nisayah, or the Democratic Arab Women Movement in Nazareth (5).

“The Golan Heights: the first moment of love with Syria and the Syrians":

Through her activism and mobilization, Samira met with fellow activist and Jawlani women rights advocate Amaly Qadamani, both forging a new path for women-led mobilization and political activism. As Samira shares (6):

“After the occupation of the Golan Heights in 1967, we organized regular visits to Majdal Shams to coordinate and meet with our colleagues like Emilie Kadamani and Amal Abu Jabal and others. We also invited them to come to Nazareth for regular meetings to cook and discuss together how to build our mobilization. We started to protest with them against the occupation in a partnership with our Jewish colleagues. Different charters of the Democratic Women Movements in Rameh, Akko, and the triangle also organized bus trips to Majdal Shams. During the early days of the siege, we used to organize daily visits to demonstrate against the unlawful situation there and we even set up a demonstration tent in Nazareth in Al Ain Square.”

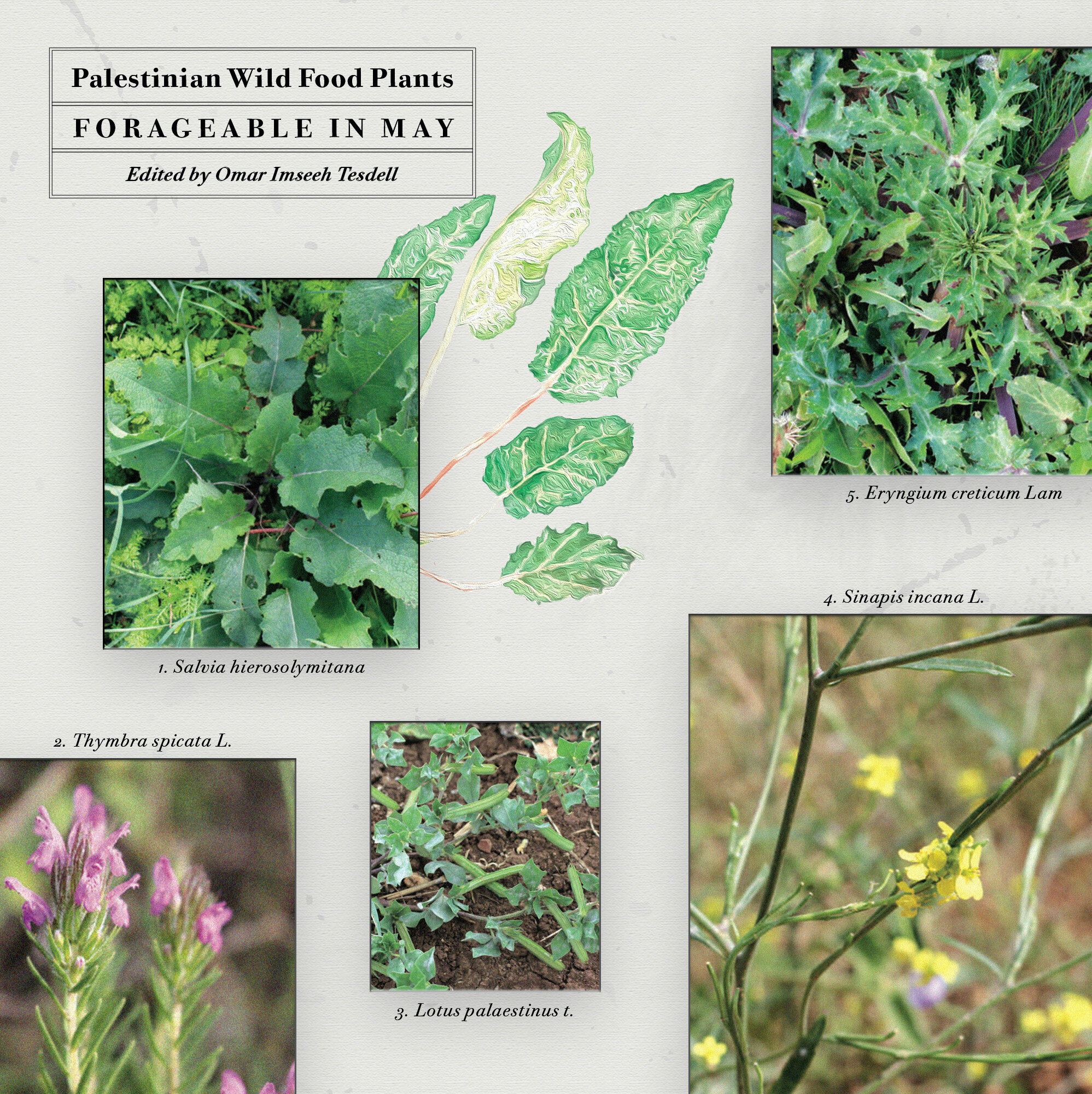

Solidarity visit of the Democratic Women Movement in solidarity with women of the Golan in 1976 (7)

International Women’s Day march in Yafa in 1986 with a message to women in the occupied Jawlan (8)

Meeting between the Democratic Women Movement and Women from the Golan (9)

Samira highlights that a turning point in the solidarity work to support Syrian Jawlanis steadfastness against the Israeli occupation was when support with marketing their apple products began taking shape in a more organized matter. In Nazareth as well as in Jenin, Nablus, and Gaza, Palestinian merchants and activists began promoting and marketing Jawlani agricultural crops, such as apples and peaches, to support them and their fight to remain on their land.

The relationships that Samira and her colleagues have nurtured throughout the decades with Jawlani women and their families remain strong and warm. She proudly displays an appreciation plaque gifted to her by ‘The Women of the Golan’ for all her efforts and determination to create bridges of solidarity, mutual aid, and unconditional dedication to justice and peace.

Appreciation plaque at Samira Khoury’s residence in Nazareth (10)︎︎︎

Common struggle and solidarity budding inside prison walls

“The prison experience in the 1970s, in my opinion, was the most critical and central stage in Palestinian-Jawlani relations. That was a truly collective experience that transformed our political relations and struggles,” Salman Fakhreldin, a political figure in the Jawlan and human rights activist working for decades to raise awareness of Israeli human rights violations, exclaims (11). Jawlani and Palestinian prisoners were meeting, sometimes for the first time, inside prison walls and learning about each other’s struggles, mobilizing their communities when escalations and clashes arose and participated in acts of solidarity inside the prison commemorating important events. One example is narrated by Hayl Abu Jabal, a veteran political figure in the Jawlan, who reflects on the reciprocal nature of the Jawlani-Palestinian struggle and solidarity. In a post last year on Facebook, Hayl recalls the events of the 1976 Land Day while imprisoned in Ramleh for his role in a secret cell operating from the Jawlan and cooperating with the Syrian intelligence forces. After announcing a strike commemorating the first anniversary of Land Day, the bewildered prison authorities wondered why Syrians would do that? They are not Palestinians! Hayl recalls the reply of Shakib Abu Jabal, a renowned political figure and leader who said firmly: “It seems you don’t comprehend that Palestine is southern Syria!”

March in the Golan Heights in solidarity with Land Day demonstrators and martyrs (12)

Hayl Abu Jabal post reflecting on solidarity with Palestinians in the 1970s

Solidarity with Birzeit University - an unlikely beginning:

“Relations with the university began through the shortest and the most unlikely way we can imagine,” is how Salman Fakhreldin started his conversation about the relationship between Birzeit University and the Jawlanis (13). This relationship started through the Jewish solidarity committee with Birzeit University in the 1970s, which was a committee including Jews and Arabs headed by the physics professor Danny Amit at Hebrew University. We started to get acquainted with them, especially the Jerusalem group. That is how I learned about Birzeit University and their role in leading a popular struggle against the occupation.” In the eighties, the Jawlan and Birzeit University shared common strategies of resistance. In the Jawlan, Salman was heading the media committee that played a critical role in raising awareness about the events of the strike, the siege in Palestine, and beyond.

During that time, Salman was invited to attend a meeting in Jerusalem with the Birzeit Solidarity Committee to share about strikes in the Golan Heights and their aims. While solidarity demonstrations, visits, and financial and political support were consolidated in the 1980s by Palestinians and centered around breaking the siege, voluntary work camps organized by Birzeit University were the highlight of that relationship. From 1985 to 1987, the student council and the voluntary work department organized visits to the Jawlan to support the farmers during apple, peach, and cherry harvesting seasons. Every season, between 150-250 students arrived at the Golan Heights to participate in volunteer work camps, that were in essence political and spaces to learn about each other’s struggle against the occupation. Ali shares how these camps were so influential for solidifying solidarity between Jawlanis and Palestinians: “It was an opportunity to get acquainted with that area, since the Jawlan is far away, and only those who go to visit that area go to Jabal el Sheikh as a touristic area and do not visit the Arab villages in the Jawlan. These visits allowed us to create a brotherhood between Palestinians and Syrians from the occupied Golan outside the prison walls.”

Salman Natour on intersectional struggle: “I’m not from the Jawlan but my heart is with the Jawlan”

Salman Natour (14)

Salman Natour was a Palestinian writer and freedom fighter from the village Daliyat al Karmel near Haifa (15). He was born a year after the Nakba and was active in the communist party, the only party where Palestinians inside Israel could become politically mobilized. Salman embodied the essence of Palestinian-Syrian Jawlani solidarity. As a journalist, he contributed to numerous articles about the Golan Heights, especially at the height of the 1982 general strike event and siege. He was also the secretary of the Committee for Solidarity with the Golan which he initiated with monumental figures such as Emile Touma (a Palestinian historian, journalist, and the co-founder of Al-Ittihad newspaper). The committee mobilized lawyers, physicians, and politicians across the Galilee, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip to support the Jawlanis through organizing demonstrations, solidarity visits, and medical and food support in an effort to break the unlawful siege they were undergoing by the Israeli military forces.

Salman Natour’s article in March 1982 urging the world to pay attention to the siege in the Golan Heights (16)

His articles were poignant and powerful documentation of events he witnessed when he was able to reach the Jawlan, combined with testimonies he collected from the Jawlanis themselves. These testimonies depicted critical moments in the strike, such as the collective act of throwing the Israeli identity cards authorities tried to impose on the Jawlanis and they vehemently refused.

Iconic photo of collective throwing of the Israeli identity cards in 1982 (17)

Salman continued his mobilization efforts through his attempt to testify before the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva on the conditions of Arabs in occupied territories. However, the Israeli authorities issued a travel ban on Salman and confined him to his village for six months where he couldn’t even continue visiting the Jawlan (18).

Natour writes at the 1st anniversary of the strike (Al-Ittihad, 15 February 1983) (19)

Salman’s mobilization with the Jawlanis was not limited to the strike and he continued to document and commemorate the anniversary with his counterparts. During an event in Majdal Shams celebrating the 31st anniversary of the strike, he spoke of the strike as the most fascinating period of his life, when the collective struggle of Palestinians and Jawlanis solidified and transcended artificial borders created by settler colonialism (20).

Salman expresses the centrality of the strike in his life by reiterating, “As an author, politician, as an Arab and a Palestinian, I carry the Jawlan strike experience with me wherever I go.”

FOOTNOTES:

(1) For more information, check the project’s website here.

(2) New Directions in Palestinian Studies (NDPS) carried out its fifth annual workshop in March 2018 at Brown Univeristy and was entitled “The Shadow Years: Material Histories of Everyday Life,”. This workshop attends to Palestinian experiences overshadowed by the overwhelming focus on moments of rupture such as 1917, 1936–1939, 1948, and 1967.

(3) National Library of Israel. 1974. https://rosetta.nli.org.il/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE45740676

(4) Interview with Muna Dajani. Summer 2017.

(5) Eventually, The Movement of Democratic Women in Israel emerged as a collaboration and integration of two movements: The Democratic Arab Women Movement and The Progressive Jewish Women Movement. Rosa Luxemburg website. Tandi movement of democratic women in Israel. https://www.rosalux.org.il/en/partner/tandi-movement-of-democratic-women-in-israel-mdwii/

(6) Interview carried out by Alaa Iktaish on 13 March 2021 in Nazareth.

(7) The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive. https://palarchive.org/item/133923/the-movement-of-democratic-women-stands-in-solidarity-with-the-women-of-the-golan-1976/

(8) The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive. https://palarchive.org/item/133916/the-8th-of-march-demonstration-1986/

(9) The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive. https://palarchive.org/item/128744/a-meeting-between-the-movement-of-democratic-women-and-women-from-the-golan/

(10) Photo taken by Alaa Iktaish. March 2021.

(11) Interview with Salman Fakhreldin conducted by Diaa Ali Hroub.

(12) Photo from Jawlan.org. Retrieved in 2017.

(13) Interviews conducted by Diaa Ali Hroub in 2020.

(14) Retrieved from arab48 website. 2017. https://www.arab48.com/فسحة/جدول/2017/07/15/في-ذكرى-ميلاده-أمسية-لسلمان-ناطور-في-الجولان-|-مجدل-شمس

(15) Research conducted by Bassel Rizqallah.

(16) Al-Ittihad newspaper. 12 March 1982. 13 thousand detainees appeal to the free of the world. P.7. Retrieved from National Library of Israel archive. https://jrayed.org/ar/newspapers/alittihad/1982/03/12/01/?&e=-------ar-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxTI--------------1

(17) National Library of Israel. 1982. https://rosetta.nli.org.il/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE45841858

(18) Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 1982. Jta daily news bulletin. May 13 1982. Vol. LX, No. 92, p. 3. Retrieved

http://pdfs.jta.org/1982/1982-05-13_092.pdf?_ga=2.177702061.948891012.1619832444-1786531834.1619832444

(19) ص2، لو اعتقلتمونا جميعا وسننتم الف قانون فلن تستطيعوا تغيير جنسيتنا السورية، سلمان ناطور https://jrayed.org/ar/newspapers/alittihad/1983/02/15/01/?&e=-------ar-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxTI--------------1

(20) Aiman Abu Jable YouTube Channel. 2013. مداخلة الكاتب سلمان ناطور في ذكرى انتفاضة الجولان، يوتيوب: قناة أيمن أبو جبل، تاريخ النشر: 15 فبراير 2013، تاريخ الوصول: 30 أبريل 2021، في:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYf7pkQyBls&t=1s

'Palestine, IN-BETWEEN' is presented by CPS + LIFTA with Lena Mansour and Cher Asad with support from The Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities, the Center for Archaeology at Columbia University and the Columbia Global Center | Amman.